|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

the rosetta stone Please maximise this browser window for best results

The importance of the Rosetta Stone lay in the fact that the Egyptian hieroglyphic text was accompanied by the Greek translation which could be read and understood by scholars. A third inscription on the stone was written in Demotic, a cursive script developed late in Egyptian history and used in most cases only for secular documents. The inscription on the stone was a decree passed by a general council of priests which assembled at Memphis on the first anniversary of the coronation of thirteen year old Ptolemy V Epiphanes, king of all Egypt. The text concerns the honours bestowed on the king by the temples of Egypt in return for services rendered by him to Egypt, both at home and abroad. Priestly privileges, particularly those of an economic nature, are listed in detail. In previous years the family of the Ptolemies had lost control of certain parts of the country. It had taken their armies some time to put down opposition in the Delta, and parts of southern Upper Egypt, particularly Thebes, were not yet back under the government's control.

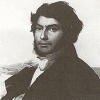

Thomas Young was the first scholar to prove that the elongated ovals (known as cartouches) in the hieroglyphic section of the Rosetta stone contained a royal name that was written phonetically, in this case, that of Ptolemy. Jean François Champollion went on to correct and enlarge Thomas Young's list of phonetic hieroglyphs and lay the foundations of our knowledge of the ancient Egyptian language. His first major breakthrough came when he pieced together the alphabet of hieroglyphs that was used to write the names of non-Egyptian rulers. His paper was read to the "Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres" in Paris in 1822. He made a second crucial breakthrough in 1824, when he realised that the alphabetic signs were used not only for foreign names, but also for the Egyptian language and names. Together with his knowledge of the Coptic language, which derived from ancient Egyptian, this allowed him to begin reading hieroglyphic inscriptions fully.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Rosetta Stone is a black basalt slab bearing an inscription dating from the year 196 BC. It was the crucial key to the deciphering of Egyptian hieroglyphs, and the foundation of modern Egyptology. The stone was discovered in 1799 by the French troops in Napoleon's military expedition. They were digging the foundations of an addition to a fort near the town of el-Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta, Lower Egypt. During the treaty of Alexandria in 1801, the stone was ceded to the British, and has been in the British Museum in London ever since. An exact copy of the stone is on display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

The Rosetta Stone is a black basalt slab bearing an inscription dating from the year 196 BC. It was the crucial key to the deciphering of Egyptian hieroglyphs, and the foundation of modern Egyptology. The stone was discovered in 1799 by the French troops in Napoleon's military expedition. They were digging the foundations of an addition to a fort near the town of el-Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta, Lower Egypt. During the treaty of Alexandria in 1801, the stone was ceded to the British, and has been in the British Museum in London ever since. An exact copy of the stone is on display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.