|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

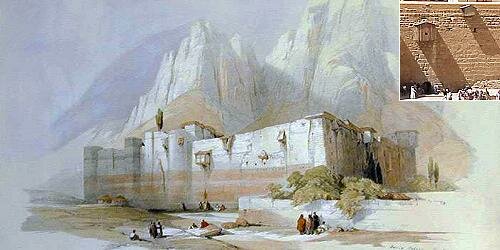

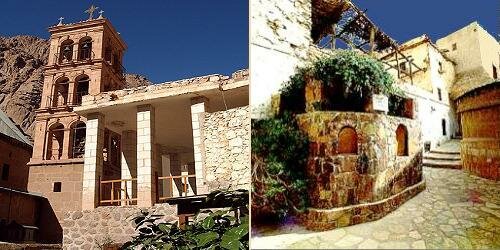

The Greek Orthodox monastery of St Catherine stands at the foot of Mount Horeb (Jebel Musa) in a small gorge in the wilderness of Sinai. This is where, according to the Old Testament, that Moses received the "Tablets of the Law". St Catherine's, founded in the 6th century, is one of the oldest Christian monasteries still in use as a working monastery today. Its walls and buildings are of great significance in the study of Byzantine architecture and it houses outstanding collections of early Christian manuscripts and icons. The rugged mountainous landscape, featuring numerous archaeological and religious sites and monuments, forms a perfect backdrop to the monastery. St Catherine's is one of the very early outstanding examples in Eastern tradition of a Christian monastic settlement located in a remote area. It demonstrates an intimate relationship between natural grandeur and spiritual commitment. Ascetic monasticism in remote areas prevailed in the early Christian church and resulted in the establishment of monastic communities in remote places. St Catherine's is one of the earliest of these and the oldest to have survived intact, being used for its initial function without interruption since the 6th century.

Saint Catherine the person

The legend tells us that Catherine was the daughter of Constus, governor of Alexandria in Egypt. Well educated and of high status, she is said to have declared that she would only enter into marriage with someone who surpassed her in reputation, wealth, beauty and wisdom. Catherine's mother was secretly a Christian, and sent her to a hermit who told her of a youth who surpassed her in everything, such that "His beauty was more radiant than the shining of the sun, His wisdom governed all creation, His riches were spread throughout all the world." Having prayed and received a vision that urged her baptism, she became a Christian, and is said to have visited the Roman Emperor to convince him to stop his persecution of the Christians. Catherine succeeded in converting the emperor's wife, together with many officials, originally sent by the emperor to dispute with her. Exasperated, the emperor had Catherine imprisoned, but when she continued to convert his subjects, she was finally sentenced to death on the "breaking wheel" a notorious spiked wheel used for torture (see below). Ironically, the wheel itself was said to have broken when she touched it, so she was beheaded instead (there's fate for you!). Her principal symbol is the spiked wheel, which has become known as the Catherine wheel, and her feast day is celebrated on the 25th November in most Christian churches.

The Monastery of the Transfiguration The monastery was built under the orders of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I between 527 AD and 565 AD, in order to safeguard and protect the gathering of monks and hermits living in nearby caves and simple huts. A significant fortification was built under the guidance of architect Stephanos of Aila, enclosing an earlier Chapel of the Burning Bush that had been built during the time of Helena, the mother of Constantine I. The chapel marked the spot at where Moses is supposed to have seen the burning bush - the living bush on the grounds today is allegedly the descendant of that very same original.

The heavily fortified monastery gave protection to the monks, with thick granite walls ranging in height from 8 to 35 metres tall. Up until sometime during the 20th century, the only entrance to the monastery was a small covered defensive machicolated "trap door" set 30ft high up in the walls, where people and provisions could be lifted up and lowered using a systems of pulleys and baskets (see David Roberts lithograph above). The monastic church, dates from the reign of Justinian and is a three-aisled, wood-roofed, basalt basilica. The basilica has five side chapels, and towers flank the west end of the church. The earlier chapel of the "burning bush" was incorporated into it, whilst the sacred "burning" bush itself is left growing in the open beyond the east end of the building.

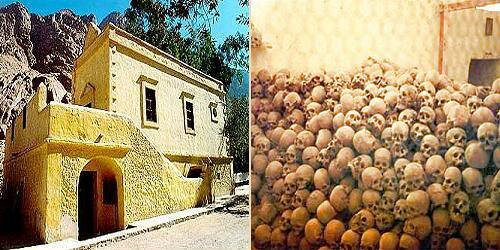

The monastery church has seen little essential change since the time of its founder. Its great western doorway is still closed by the original 1400 year old Lebanese cedar wood doors, still functioning on its first pins and hinges. The wooden roof of the nave, also of 6th century construction, rests on beams that bear inscriptions honouring Justinian and his famous wife the Empress Theodora. The inscriptions mention "our most pious Emperor" and his "late Empress". Theodora died in 548 AD and Justinian in 565 AD, therefore one can assume that the church was completed between those years. Also within the monastery's walls stand the remnants of a 10th or 11th century Fatimid mosque, possibly built to conciliate the Muslim authorities of the time. Recent excavations within the mosque's walls have produced evidence that the building predates its use as a mosque - architectural and ornamental crosses together with other Christian symbols have been discovered within. It is thought that a muslim garrison may have been stationed at the monastery during the Crusades. Outside the enclosure of the monastery lie the gardens - a true oasis in a landscape of desolate rock. These ancient gardens provide vegetables, decorative plants and flowers, olive trees, apricots, plums and cherries - all grown on soil tirelessly brought in from afar by the monks, and tended with great care and reverence. In the gardens there is also a small area that is used as a cemetery, and a small chapel dedicated to St. Tryphon that serves as an ossuary for the skulls of the deceased monks.

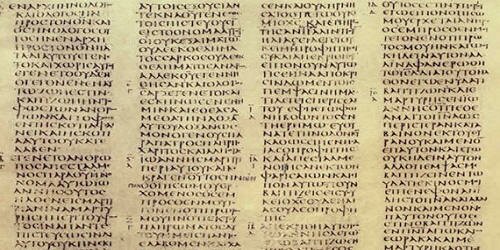

Manuscripts and icons St Catherine's is a spectacular natural setting for priceless works of art, including Arab mosaics, Greek and Russian icons, Western oil paintings, paintings on wax, fine sacerdotal ornaments, marbles, enamels, chalices, reliquaries, including one donated by Tsar Alexander II in the 19th century, and another by Empress Catherine of Russia in the 17th century. But of perhaps even greater significance is that it holds the second largest collection of illuminated manuscripts (the Vatican has the largest). This truly amazing collection consists of some 3500 volumes in Greek, Coptic, Arabic, Armenian, Hebrew, Slavic, Syriac, Georgian and other languages. Many of the manuscripts in the collection are illuminated with rare and fine miniatures. In addition to the manuscripts, the library contains a sizeable number of printed books, of which around 5000 are old editions dating from the earliest days of the art of printing. The library is now equipped with laboratories for the conservation and the microfilming of manuscripts, and its archives are available for use by scholars engaged in special studies. Around the year 1850, the fourth century Codex Sinaiticus was discovered here by the German biblical scholar Constantine Tischendorf. During three separate visits to St Catherine’s, Tischendorf had several portions of the Codex brought to his attention by the monks there, which he subsequently "borrowed" and took back to Leipzig University where he was a professor. In 1859, Tischendorf presented a considerable portion of the codex to Tsar Nicholas II as a gift, which was later acquired by the Imperial Russian Library in St Petersburg. This portion of the codex was later sold by Stalin to the British Library for £100,000 to raise much needed foreign capital.

Just over half of the original book has survived, now dispersed between four institutions: St Catherine’s itself, the British Library, Leipzig University Library in Germany, and the National Library of Russia in St Petersburg. At the British Library the largest surviving portion – 694 pages – includes the whole of the New Testament. Despite its rather austere appearance, the Codex Sinaiticus is a treasure beyond price. Produced in the middle of the fourth century, the Codex is one of the two earliest Christian Bibles (the other being the Codex Vaticanus in Rome). Within its beautifully handwritten Greek texts, is the earliest surviving copy of the complete New Testament, together with the earliest and best copies of some of the Jewish scriptures in the form that they were adopted in by the Christian Church. As one of the earliest luxury codices to survive in large part, the Codex forms one of the most important landmarks in the history of the book. A team of experts from the UK, Europe, Egypt and Russia is currently digitising the parchment, as the oldest known Biblical New Testament in the world is set to enter the digital age and become accessible online. This international project aims to make accessible and reinterpret the Codex Sinaiticus for a worldwide audience of all ages and levels of interest, employing cutting-edge new technology and advanced scholarship.

In addition to the fantastic collection of manuscripts in its library, the monastery has one of the most important collections of icons. Numbering over 2000, many of these are unique masterpieces in their own right, whilst others are simple works of art. They are spread throughout the complex - the basilica, the chapels, the icon gallery, the sacristy and even in the monks' own cells. They were produced during various periods between the 6th and 19th century, with every period adding new treasures to the monastery's vast collection. The earliest icons were produced using the encaustic technique, which was used until the 7th century AD, when it was replaced by the secco or tempera painting. The monastery has a number of important encaustic icons which were produced by local workshops active in monasteries of the East, particularly Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Cappadocia. They are products of folk art, less refined in character, and make use of a primitive realism to give expression to the local tradition of the Coptic and Syrian Churches. These rare icons have been one of the main sources that contributed in shaping Christian art during the following centuries. Later icons, produced between the 9th-12th centuries, adopted a more classical concept of art that is reflected within the delicacy of the drawing and the beauty of the form. These icons were mainly produced in the imperial ateliers of Byzantium and include portraits of Christ, the archangels, saints, hierarchs and hermits. Illuminated manuscripts were produced in great numbers during this period, including Gospel-books, synaxaries and other texts, and the very significant art of miniature painting had a more general influence on iconography. Pilgrims

In the 1950’s, the roads that led to the oil fields and mines along the western coast of the Sinai were paved by the Egyptian government. The government also developed a dirt track to the foot of Jebel Musa and the monastery. This provided an easier access for a new wave of tourists to travel to the monastery in taxis from Cairo. Later on, the completion of a paved road to Jebel Musa further improved access for an ever-growing number of visitors, both secular and religious. The introduction of a regular bus service from Cairo in 1986 has since amplified tenfold the number of tourists to the site, and today it is not uncommon for a hundred or more people to visit the ancient monastery in just a single day. Currently Greek Orthodox monks tend the monastery and its extraordinary collection of Byzantine art and illuminated manuscripts. In June 2002, the monastery of St Catherine's was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Thanks to: The British Library, UNESCO World Heritage Centre, TourEgypt. Return to Coptic monasteries >>

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Saint Catherine was a Christian martyr initially sentenced to death on the wheel. However, when this failed to kill her, she was beheaded. According to tradition, angels took her remains to Mount Sinai. Around the year 800 AD, monks from the monastery purportedly found her remains at the top of the peak that now bears her name.

Saint Catherine was a Christian martyr initially sentenced to death on the wheel. However, when this failed to kill her, she was beheaded. According to tradition, angels took her remains to Mount Sinai. Around the year 800 AD, monks from the monastery purportedly found her remains at the top of the peak that now bears her name.

Throughout the 14th century, many thousands of pilgrims came annually to visit the monastery, regardless of the fact that it was an arduous eight-day journey by camel from Cairo. Following on from the time of the Reformation though, the popularity of the Christian pilgrimage took a dramatic downturn, with the number of pilgrims gradually declining until around the mid 1900’s when the journey was completed by fewer than a hundred people each year.

Throughout the 14th century, many thousands of pilgrims came annually to visit the monastery, regardless of the fact that it was an arduous eight-day journey by camel from Cairo. Following on from the time of the Reformation though, the popularity of the Christian pilgrimage took a dramatic downturn, with the number of pilgrims gradually declining until around the mid 1900’s when the journey was completed by fewer than a hundred people each year.