|

|

|

Pages in this article: [ MEDICINE ] [ THE PHYSICIAN ] [ THE DENTIST ] [ TREATMENTS & SURGERY ]

The dentist

Dentists were known to have existed in Egypt since the Old Kingdom. The first reference to the title "dentist" was given to the physician and scribe Hesy-Re c.2650 BC.

|

x |

Herodotus mentions the names of fifty physicians who bore the title "dentist".

Within dentistry there were two classes, the lower being "iryw-ibew" meaning "dentist", whilst the elite were referred to as the "ir-iryw-ibew" meaning either "great of those who are concerned with teeth" or "great of dentists".

Dental specialists practiced their art within the confines of the royal court, whilst the ordinary common man had to rely on the "swnw" (the basic "doctor of the people") for their dental treatment.

|

| The physician and scribe Hesy-Re. |

|

|

|

In Ancient Egypt, however, the mere possession of an official title offers no guarantee that its owner engaged practically in the suggested subject. It is quite possible that any practice of dentistry may have been limited to the use of the prescriptions in the medical papyri.

The Ancient Egyptian dentists were researchers rather than therapists, who wrote down their observations in great detail. To these, they could then conceive a treatment, usually based on a trial and error system. The dentist's main aim was to prevent, rather than cure an ailment.

|

|

|

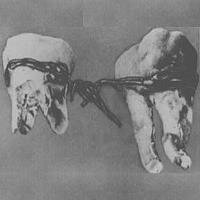

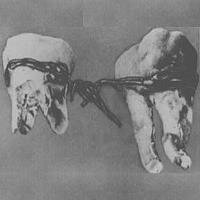

Teeth wired together.

|

The Ebers Medical Papyrus-suggests ten remedies for "keeping a tooth in good condition". One such remedy thought to describe a filling, although not corroborated, prescribes:

|

Resin of terebinth: "1; Nubian Clay: 1; green eye lotion: crush together and (or apply) to the tooth"

|

Due to the widespread nature of dental disease, halitosis (bad breath) must have been a common complaint. As such, a recipe has been discovered to combat this condition:

|

Breath Sweetener: "Take frankincense, myrrh, cinnamon, bark and other fragrant plants, boil with honey and shape into pellets".

|

One of the most powerful tools in the dentist's armoury was magic. If his treatments were deemed not to be working, the dentist could call upon magic formulae for destroying "the enemy which is in the tooth".

The teeth were associated with the creator god Ptah. Situated inside the god's mouth which brought existence into being, the teeth took part in the act of creation, and as such were regarded as an important element to the pronouncement of words.

The nature of dental dieseases

by J D MUIR BDS., FDS. M.ORTH. RCS

Throughout human history certain recognised diseases and processes have affected the teeth and their supporting structures. I will discuss the most common in general terms and consider them in the context of the Ancient Egyptians.

|

CARIES: Bacteria, which is normally present in the mouth, builds up on tooth surfaces in the form of dental plaque. They convert food sugars into acid, which is released against the enamel surface. The enamel is progressively destroyed by the acid attack until the process reaches the dentine.

As dentinal caries advances, the tooth is likely to become sensitive to sweet, sour and salty foods. The pulp defends itself by retreating as it lays down secondary dentine but, if the process continues, there will later be pain upon hot and cold stimuli which, as the infection reaches the pulp, will become continuous and severe.

Commonly, the cavity in the tooth will be readily evident clinically by this stage.

|

|

Eventually, the pulp dies and the pain ceases. In time, however, bacterial toxins may pass through the apical canal of the tooth and produce bone destruction around the apex. The tooth may become sensitive to pressure. Still later, bacteria will emerge and produce an apical abscess. Bone will be destroyed around the root. Facial swelling may occur and pus may track through a sinus to discharge into the mouth or even onto the face.

|

Dental caries has been described as a disease of civilisation. This is because its incidence is related to the proportion of sugars and refined carbohydrates in the diet. In Victorian times there are reports of a class difference in the incidence of caries in children, because wealthier families could afford confectionary.

|

|

The nature of the diet means that the incidence of caries in ancient times was lower than in recent times. The few sources of available sugar for the Egyptians would have included figs and dates, but the most effective sweetener would have been honey, which is likely to have been affordable only by the rich.

|

Caries, when it did occur, was commonly in the cervical area of the tooth (around the gum margin). A large proportion of the Ancient Egyptian diet was bread, made from emmer wheat, and this is apparently particularly sticky. It could be that the pattern of caries was influenced by the tendency of this material to adhere to the teeth.

|

TOOTH WEAR: This term includes attrition (wear during chewing) erosion (chemical attack, e.g. from acidic fruit juices or gastric reflux) and abrasion.

In today’s society, loss of enamel can result from many varied factors including acidic drinks and “bingeing”. In historical times tooth wear was chiefly produced by chewing, and its severity is related to the abrasiveness of the diet and to the age of the individual.

Human remains from Ancient Egypt commonly demonstrate very severe tooth wear. Much of this must have resulted from the sand and grit which will inevitably have found their way into everything, including food. The actual stone of the mill or quern would also contribute some particles.

|

|

Beyond this, it seems likely that sand or chalk may have been deliberately introduced into the process of milling to improve its effectiveness. Emmer wheat is said to have higher silica content than other types and this, too, will have caused increased wear. If the rate of tooth wear is very rapid the dental pulp may become exposed and, as a result, infected. This can result in death of the pulp and subsequent abscess formation similar to that produced by dental caries.

Many of examples of such bone destruction found in the jaws of Ancient Egyptian skulls derive from tooth wear rather than caries. Whatever the cause, the affected tooth could remain firm for a long time. An unenviable situation can occur with pus discharging, producing an unpleasant taste to the sufferer and an offensive smell to those around. A carious tooth may eventually decay sufficiently for it to break up and for the fragments to be shed naturally.

|

PERIDONTAL DISEASE: This attacks the supporting tissues of the teeth, (the gum and the bone). Bacteria in the plaque around the gum-margin cause inflammation at the edge of the gum (marginal gingivitis). Other opportunistic bacteria may later invade to break down the attachment of the supporting tissues to the tooth and produce pockets between the tooth and the gum. The deposition of tartar (from mineral salts in the saliva) onto the tooth surface can extend into the pockets. Progressive bone loss can occur, followed by loosening, drifting and eventual loss of the teeth.

A major dental health measure today is the use of a toothbrush and floss. These can prevent the build up of plaque on flat tooth surfaces and contribute to the prevention of caries and periodontal disease.

|

|

There is no knowledge of any oral hygiene regimes in Ancient Egypt except for the occasional use of natron pellets as "masticatories" (almost as an equivalent to chewing gum).

A problem with skeletal remains

The fact that one or more teeth are missing from a dry skull may not mean that they were lost before death. Teeth, and particularly single rooted anterior teeth, may be readily displaced post-mortem. In such a situation, however, the tooth sockets will be clearly defined with sharp margins.

Where teeth have been lost before death, the sockets become shallower and their margins more rounded. With time, the alveolar bone (the ridge of bone which exists to support the teeth) shrinks and the sockets will eventually disappear altogether in five to seven months.

|

DENTAL TREATMENT: Some effective medical treatments have been achieved empirically after good observation, (e.g. Jenner’s development of vaccination for smallpox). Generally, however, the treatment of any disease, if it is to be effective, demands some understanding (even if very imperfect) of the disease process involved (and the aetiology of dental caries was believed to be "the tooth-worm").

Furthermore, technical intervention demands the ability to manufacture instruments of sufficient quality to carry out any required tasks.

|

|

It has been asserted that various clinical procedures were carried out in Ancient Egypt.

Such claims have included: fillings, bridgework, root-fillings, extractions and the draining of abscesses through bone, but clear evidence of operative dental intervention is lacking. This is not surprising when one considers that, for example, it was only in the late nineteenth century that right-angled drills capable of cutting enamel became available. Similarly, no ancient instruments capable of extracting a firmly attached tooth have ever been discovered.

A recently claimed example of the enucleation (surgical removal prior to eruption) of upper premolar teeth in a child of the Græco/Roman period appears more likely to be the result of post-mortem loss.

|

Loosening teeth may be removed with the fingers. The Ebers papyrus deals sensibly with the treatment of a dislocated mandible, whilst recommending that a compound fracture of the mandible should not be treated (perhaps because death was likely to follow after septicaemia). The lancing of an abscess in soft tissue would have been within the capability of an ancient physician but any more sophisticated procedures probably only existed in the Græco-Roman period and were fairly rare even then.

|

|

It seems likely that, apart from simple procedures, treatment for dental ailments was limited to the use of magical incantations and the sort of prescriptions contained within the various medical papyri. One recipe to treat toothache requires beans to be ground up with another substance. The word is missing but it is possible that it could be "willow" from which aspirin was originally obtained. Other mixtures seem likely to have hardened after preparation and might have been used to splint loosening teeth. Honey, which is included in several recipes, has been shown to have an antibacterial effect. But much conjecture must remain. The terms used may make translation uncertain, the identification of herbs and substances may be inaccurate.

What is certain, however, is that the Ancient Egyptians suffered from extensive, severe and painful dental disease which the available treatments of the time can have done relatively little to alleviate.

| The Nature of Dental Disease was kindly written by J.D. Muir BDS., FDS. M.Orth. RCS. He is one of the country's leading orthodontists, who regularly acts as an advisor to the archaeologist Barry Kemp. |

Treatments >>

|

|

|