|

|

|

Understanding Egyptian chronology, by Tony High

Chronology | Towards a unified chronology | A new chronology

The highly complex subject of Egyptian chronology is fraught with problems, due in part to the Egyptian regnal dating system. The Egyptian system appears devoid of any form of continuity as used by other Near Eastern cultures; instead of a continuation with each successive ruler, the count was "reset" with the inauguration of each successive pharaoh. As a result, the chronologer is forced to compile a list of pharaohs determined partly on archaeological finds that include tablets and statues, with inscriptions, pottery fragments, tomb relics and hieroglyphic inscriptions such as the Turin King’s List and the Abydos Kings' List.

|

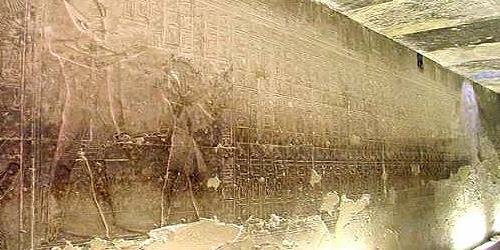

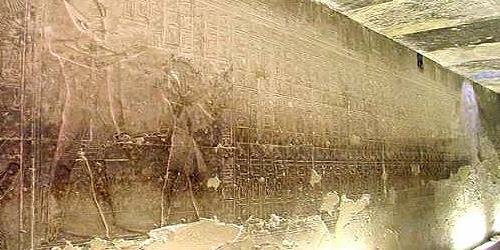

| The Royal List of Abydos. In the Hall of the Records at the Temple of Abydos, Seti I and his young son the future Ramesses II, are shown worshipping the cartouched names of 76 of their ancestors. However, "unacceptable" predecessors, such as Hapshepsut and Akhenaten are conveniently omitted from this list. The list also does not have records of any of the kings from the Second Intermediate Period. A badly damaged duplicate of the Royal List of Abydos known as "The Abydos Kings' List" was also discovered in the nearby temple of Ramesses II. |

The lists, although useful as a reference, are by no means complete, have significant gaps and heavily favour the Memphite kings; in some instances failing to provide a complete list of rulers, even for a short period of Egyptian history. Moreover, during the First Intermediate Period there were three rival kingdoms, Memphis, Thebes, and Herakleopolis. None of the Herakleopolitan kings are included in the Abydos list and it is only after the Memphite line ceased to exist and Montuhotep I reunited Egypt, that the Theban kings are included.

Co-regencies

The Egyptians, at certain times throughout their history, also adopted a policy of co-regencies with some reigns overlapping, and sometimes even running concurrently. As a result, the chronologer is forced to compile a list of pharaohs, determine the length of their reigns, and adjust for any inter-regnums (the period of time between the end of one reign or regime and the beginning of the next) or co-regencies. In order to integrate the knowledge as a whole, reference is made to the works of early historians, who often used ancient records not available to us today, namely the Egyptian historian Manetho’s "Corpus Aegyptiaca" - the first to divide Egyptian rulers into thirty-one dynasties, together with further reference made to the works by other eminent historians such as the works of Eusebius, "Evangelicae Preparationis" and Sextus Julius Africanus, the history of the world "Chronografiai", in five books.

Historical Pillars

Unfortunately, for almost all kings of Egypt, we lack an accurate count for the length of their reigns, with dates for the same pharaoh often varying substantially depending on the referring source. In order for the Egyptologist to produce a unified chronology based upon a codifiable timescale, it becomes obvious that an integration and synchronism with contemporary neighbouring civilisations' chronologies is required, using such data as battles, marriage alliances and even astronomical events. These can sometimes supply a common date that can then be used to link together known events in two or more civilisations - often referred to as "Historical Pillars". Having achieved this, the relation of these different nations can then be ascertained to some degree of accuracy.

|

| Examples of "The Amarna Letters", an important cache of documents discovered in 1887 by a village woman digging for fertiliser. There are 382 known clay cuneiform tablets, whose contents shed light on Egyptian relations with Babylonia, Assyria, the Mitanni, the Hittites, Syria, Palestine and Cyprus. They are important for establishing both the history and chronology of the period. |

The Amarna letters provide the earliest known synchronisms between Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. They provide clear evidence that the New Kingdom pharaohs, Amenhotep III and Akhenaten, were contemporaries of Kadashman-Enlil I and Burnaburiash II of Babylon, Ashur-uballit I of Assyria, and Suppiluliumas I of the Hittite empire. Further evidence of direct synchronisms between Egypt that maybe cited as a historical pillar is the peace treaty signed between Ramesses II and Hattusili III. Signed during Ramesses II's 21st regnal year, this is pretty much vouchsafe, as there exists diplomatic evidence that Hattusili III wrote to Kadashman-Turgu and Adad-nirari I of Assyria. One can therefore argue that the reign of Ramesses overlapped the reigns of Kadashman-Turgu and Adad-nirari I.

Reliability of the sources

How do we know that the sources quoted are reliable? Well, unlike the system used in Ancient Egypt, the Assyrians employed a continuous dating system known as the "Limmu", an Assyrian eponym. At the beginning of the reign of an Assyrian king, he would appoint a royal official, who would preside over the New Year festival at the capital. Each year a new "limmu" would be chosen. The Assyrians used the name of the "limmu" for that year to designate the year on official documents.

Lists of limmus have been found accounting for every year between 892 and 648 BC. Equally, there is no disagreement over the dates of the Persian, and later Babylonian kings. The "Canon of Ptolemy" lists the kings who ruled in Babylon together with the number of years they reigned, from Nabonassar in 747 BCE to the conquest of Babylon by Alexander the Great in 331 BCE. The Canon's accuracy is confirmed by the larger king lists: the principal "Babylonian Chronicle" and the Assyrian "Eponym Lists" (or limmu lists), by which Assyrian chronology is fixed from 911 BCE to 666 BCE. Some bear an important event for the previous year, and as such, are fixed with the precision of a year. The mention of the solar eclipse of the 16th June 763 BC, in the eponymy of Pur-Sagale or Bur-Sagale, fixes the reckoning for these later periods.

These two sets overlap for over a hundred years, and help to supplement each other. Synchronism is also possible with the Babylonian Empire, which, like the Assyrians, also kept detailed chronological lists. Not only have all of the year names for Hammurabi and his descendants survived more or less intact, but also a record astronomical observations were made during the eighth regnal year of Ammisaduqa, offering yet another opportunity to reliably fix chronological dates.

Three chronologies

Unfortunately, due to ambiguities in certain texts, as well as disagreements over the interpretation of the astronomical observations, there are three possible chronological dates arising for the observations. This has led to the instigation of three theoretical chronologies, which chronologers refer to and cite as follows:

- The low or short chronology: most commonly used today, sets the eighth year of Ammisaduqa at the year 1531BC as the end of the first dynasty (with a reign of King Hammurabi 1728 BC–1686 BC).

- The middle chronology: the most commonly used chronology until recently, is 64 years (one period between identical conjunctions of Venus, Sun and Moon) earlier than the short chronology (Hammurabi 1792 BC–1750 BC).

- The long chronology: 120 years earlier than the short chronology (Hammurabi 1848 BC–1806 BC).

It is therefore theoretically possible, albeit a somewhat arduous task, and fraught with differing interpretations and even misinterpretations, to produce by processing and cross-referencing various archaeological, astronomical and textual records, a universally accepted unified chronology.

A new chronology >>

|

|

|