|

|

|

Pages in this article: the discovery | the coffin | the physical remains | further examinations | reconstructions and conclusions

Compiled by Tony High

The discovery of KV55

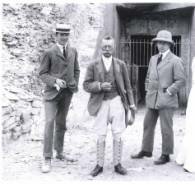

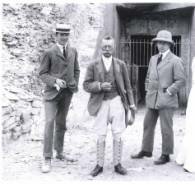

From 1902 until 1912, Theodore Davis, a wealthy American lawyer and amateur Egyptologist secured the digging concession of Biban el-Moluk, (known today as the Valley of the Kings), employing professional Egyptologists and archaeologists to help in his ventures. In January 1907, Davis employed the services of two Englishmen, archaeologist Edward Ayrton and Egyptologist Arthur Weigall.

| Whilst digging near to the tomb of Ramesses IX they discovered a series of steps. Further investigation revealed twenty-one steps that led down to a sealed entrance, comprised of a "loosely built wall of limestone fragments." [1] Behind the wall was a second partly demolished doorway, covered with hard cement and with the impression of an oval seal bearing a jackal and nine captives. This was a sign reserved for the necropolis officials, who would use it to indicate that a tomb had been resealed after an earlier warranted or unwarranted access. Past this second doorway ran a long corridor approximately six feet wide and some thirty feet in length. The corridor was filled with loose stone chippings, to within three feet of the ceiling at the entrance and to within six feet, nearest to the burial chamber. It was on these chippings, near the entrance that a wooden gilded side panel was found, along with a door with its copper pivots still in situ. |

|

|

Theodore Davis (centre) flanked by Edward Ayrton (left) and Arthur Weigall.

|

|

|

|

The corridor led to a large oblong room - the "burial chamber", some 21ft long, 16ft wide, 13ft high, and sunk 3ft below the level of the corridor. [2] Extending out of the corridor and into the burial chamber was a broad ramp, consisting of yet more stone chippings. It was on this ramp that the other door of the shrine was found, together with an alabaster vase stand. Other sections of the shrine were found leaning against the far wall of the chamber - one of the long sides lying upon the floor with wooden posts and beams scattered around it. A second chamber measuring some 6ft high by 4.5ft wide and 5ft deep, had been in the process of being hewn out of the southern wall, which had also been left incomplete. [3]

|

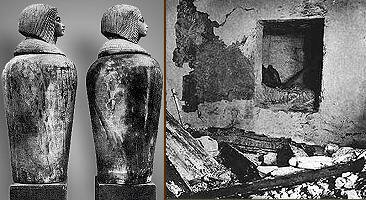

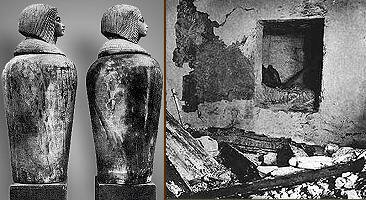

| Burial chamber of KV55. |

|

|

| It was in this recess that Davis found four, polished calcite human headed canopic jars, with the lids depicting a royal female. Below the niche on the floor were the remains of a damaged gilded sarcophagus, the occupant of which was unknown. The sarcophagus had once stood upon a lion headed bier that had become so severely damaged due to water seeping through a crack in the roof that it had collapsed, throwing off the sarcophagus lid, exposing the occupant to the elements. |

|

|

Human-headed canopic jars and the recess they were found in.

|

A thorough inspection of the chamber by Davies and his team uncovered four "magic-bricks". Three were found against the correct cardinal walls, whilst the fourth was found under the collapsed bier. On further inspection, it was found that two of the bricks were inscribed with Akhenaten's throne name "the Osiris Neferkheprure – wa-en-re." [4]

Unfortunately, the other two bricks were so badly damaged their ink inscriptions were illegible. In addition to these finds, numerous other small objects were found amongst the chippings. They included faience vessels and some small amulets discovered at the base of a wooden statue. Davis's task of trying to identify whose burial he had discovered was proving to be a rather difficult one, as the funerary paraphernalia discovered was inscribed and dedicated to more than one member of the royal family. Indeed, some of the items were dedicated to either Amenhotep III or his wife Queen Tiye, and in some cases, both. To add to the confusion, some fragments of clay seals were found containing the cartouche of Tutankhamun.

Due to the fragile nature of the funerary equipment caused by the water damage, extreme patience would be needed to successfully remove and conserve the artefacts for future investigations. Unfortunately, for us today, Davis's impatience caused much of the finds to perish before they could be properly recorded. What archaeological notes Davis did publish under the title of "The tomb of Queen Tiyi" contained very little detail and was basic in the extreme.

|

References for this page: |

| [1] |

Theodore Davis: "The tomb of queen Tiyi" London 1910 |

| [2] |

This is approx. 6.3m x 4.8m x 3.9m, with the length of the corridor measuring some 9m x 1.8m wide. |

| [3] |

1.8m x 1.35m x 1.5m |

| [4] |

Nicholas Reeves: "Egypt's false prophet Akenaten", Thames and Hudson 2001. p81 |

Next: The coffin >>

|

|

|