|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Pages in this article: [ THE LIFE OF RAMESSESS THE GREAT ] Ramesses the builder

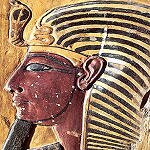

So intent was Ramesses on promoting his own image and achievements, he became increasingly impatient to see results, and he became more concerned with quantity and size rather than quality. His priority was to see his monuments completed in his own lifetime, unaware that time would be on his side. Ramesses insisted that his masons disregarded the slow and laborious method of bas-relief in favour of a new style known as sunken relief. This method was much quicker with the added bonus that it was a lot harder to delete. The same ethics applied to his monuments. Though outwardly magnificent, they were not built to the highest standards and corners were cut wherever possible. In year 2 of his reign, Ramesses altered his name to reflect his new status. His full five-fold titluary became:

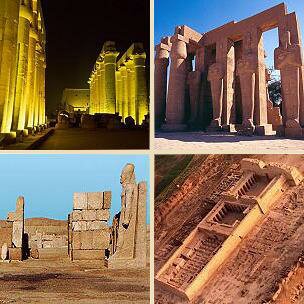

It was never too early to begin to prepare for the afterlife. Ramesses had his workers begin the construction on his mortuary temple known as the "Mansion of a million years, united with Thebes", known today as the "Ramesseum". The Ramesseum

Penra did not disappoint his king. The complex was some 300m long and 195m wide containing a landing stage, royal palace, a huge pylon entrance, two vast courts, one great hypostyle hall, three vestibules, and a sanctuary supported by four columns. Also included in the complex was a "small town", which consisted of buildings and housing for the essential religious services to the complex, such as priests, scribes, workshops, granaries, and cellars. The entire complex was enclosed behind a protective wall. The complex’s crowning glory was a colossal statue of Ramesses situated just inside the first court for all to see. It reflected the king's divine status; power and authority as it stood 17m (55ft) high and weighed an incredible 1000 tonnes! All around the complex were scenes glorifying Ramesses achievements. Most depict the king as a mighty warrior smiting his enemies. The whole of one wall is dedicated to his triumph at the Battle of Kadesh. In one scene it shows the king berating his military commanders for abandoning him on the battlefield. Another scene shows him charging into the Hittites on his chariot carving his way through anything or anybody that gets in his way.

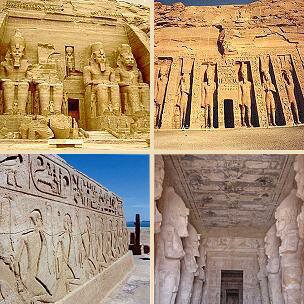

The complex was also oriented to the course of the sun, with the main access facing east so that the early morning regenerative rays of the sun would fall upon the king's statue. The layout also reflected the creation myth, with a central axis that leads to the various stages of purity, eventually reaching god. The light of the court gives way to the half-light of the hypostyle hall, which in turn gives way to the shadows of the Naos, the inner most and most sacred part of the temple. This was the "Holy of Holies" that symbolised the primeval mound emerging from the original formless ocean of chaos represented by the god Nun. It was this building that the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus referred to as the "Tomb of Ozymandias", a distortion of the name Usermaatre. Furthermore, it was the colossal, fallen pink granite statue of Ramesses that provided the inspiration for the poet Percy Bysshe Shelly to write the immortal sonnet "Ozymandias". The temples at Abu Simbel Ramesses seems to have very little regard for his predecessors and had no scruples in pulling down their monuments so that the blocks could be used to hasten his own projects. The city of Amarna was dismantled, using the stone to refurbish the city of Hermopolis. Large-scale building works were also being undertaken at Abydos, Thebes, Luxor, Pi-Ramesse, and Memphis, which was dominated by the colossal statues of the king at the Temple of Ptah. Ramesses would later have effigies of himself, shown standing next to statues of the gods at all the major temples. He was making a statement, which affirmed his status as a mortal with divine attributes. Between the regnal years 35-50, Ramesses had temples built in Nubia to supplement Abu Simbel, which due to its complexity, was started early in Ramesses's reign. His transition to full divinity was complete and this new exalted status resulted in him labelling his monuments with dedications illustrating his divine status such as "Ptah of Ramesses" in Memphis, or "Atum of Ramesses" at Karnak.

Beyond this second hall is the inner sanctum, where three divine gods sit facing the barque shrine. The three gods are Ptah, Amun-Re, and Re-Herakhty. Sitting among Amun and Re is Ramesses himself, who is proclaiming himself to be a living deity. On two particular dates, 20th February and 20th October, the rising sun moves over the horizon to gradually creep along the corridor into the inner sanctum, illuminating the four divine figures emphasising their divine nature. The siting of these temples were not accidental, far from it, they were constructed not only to glorify Ramesses but also to frighten any travellers entering into Egypt across the Nubian border. Emphasizing his authority, an inscription found near Nefertari's temple suggests that the temple was constructed using slave labour: "His Majesty brought many labourers, captives of his strong arm from all foreign lands." These colossi would confront the traveller, their size dominating and intimidating, exuding a strong, yet silent warning: "Beware you have entered the domain of mighty pharaoh." The temple of Karnak

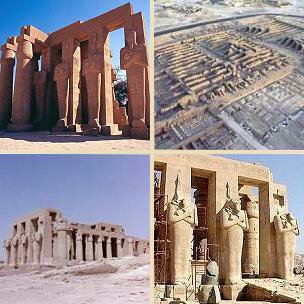

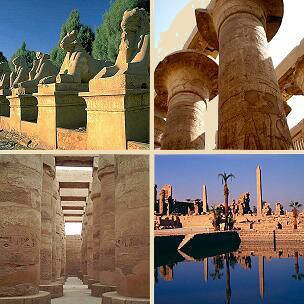

The reigns of Seti I and Ramesses II saw the construction of gigantic building projects. Seti commissioned the construction of the Great Hypostyle Hall - a vast structure composed of 134 columns, each 80 ft (25m) high. After his death, Ramesses completed his father's work, then took the credit by usurping these columns and having his cartouche deeply cut into them. Ramesses is also credited with having commissioned the "Temple of Amun who hears our prayers", the first temple at Karnak designed for popular devotion. In addition, it is thought that it was Ramesses who had the temple quay rebuilt. The Luxor temple

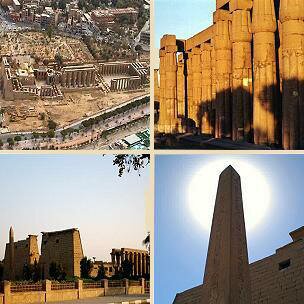

Beginning with a new temple entrance, he had a colossal pylon gateway erected, measuring some 215ft (65m) across flanked by six enormous statues of himself: two black granite seated pharaohs, whilst the other four depicted the standing pharaoh constructed from pink granite. Completing the impressive spectacle were two huge obelisks, each 25m high. Carved into the pylon walls was the ubiquitous story of Ramesses's defeat of the Hittites. This version is recorded using extravagant terminology by the scribe Pentawer, and is known as the "Poem of Pentawer". Ramesses further embellished the temple by expanding the colonnade of Amenhotep III with the inclusion of a massive courtyard, which led directly off his new pylon gateway.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

To enhance their own reputations and achievements, many pharaohs, especially Ramesses, usurped their predecessors monuments having the previous owners names and titles effaced and replaced with their own.

To enhance their own reputations and achievements, many pharaohs, especially Ramesses, usurped their predecessors monuments having the previous owners names and titles effaced and replaced with their own.  The Ramesseum was a colossal mortuary complex built on the West Bank of the Nile, dedicated to the king's Ka. Typical of Ramesses, the king instructed his architect Penra to construct the most beautiful mortuary complex Egypt had ever seen.

The Ramesseum was a colossal mortuary complex built on the West Bank of the Nile, dedicated to the king's Ka. Typical of Ramesses, the king instructed his architect Penra to construct the most beautiful mortuary complex Egypt had ever seen.

Karnak, as the cult centre of Amun, had been a centre of worship since the 9th-10th dynasty. Before the expulsion of the Hyksos, the temple was a modest affair. As sign of gratitude to Amun for successfully expelling the foreign invaders, the temple was enlarged and expanded by each successive pharaoh, until it became the largest and most important cult centre in the whole of Egypt.

Karnak, as the cult centre of Amun, had been a centre of worship since the 9th-10th dynasty. Before the expulsion of the Hyksos, the temple was a modest affair. As sign of gratitude to Amun for successfully expelling the foreign invaders, the temple was enlarged and expanded by each successive pharaoh, until it became the largest and most important cult centre in the whole of Egypt. Ramesses was obviously a man of many talents. An inscription on the entrance pylon declares that Ramesses was not only the inspiration, but also the overseer for the temple's expansion.

Ramesses was obviously a man of many talents. An inscription on the entrance pylon declares that Ramesses was not only the inspiration, but also the overseer for the temple's expansion.